So there was a bit of a dust-up in the autism community this past week. Suzanne Wright, one of the co-founders of the well-known advocacy group Autism Speaks, published an article about the group’s conference in Washington, DC. In the article, Wright characterized families touched by autism in rather vivid terms:

So there was a bit of a dust-up in the autism community this past week. Suzanne Wright, one of the co-founders of the well-known advocacy group Autism Speaks, published an article about the group’s conference in Washington, DC. In the article, Wright characterized families touched by autism in rather vivid terms:

These families are not living. They are existing. Breathing—yes. Eating—yes. Sleeping—maybe. Working—most definitely—24/7.

Wright goes on to describe the challenges that many families with autism face: financial worries, therapy challenges, concerns about their children’s health and safety, anxieties about the future. All in an attempt to rouse policymakers to come up with some kind of strategy to address the coming “national emergency” of all these autistic children growing up and becoming a huge burden on society:

Close your eyes and think about an America where three million Americans and counting largely cannot take care of themselves without help. Imagine three million of our own – unable to dress, or eat independently, unable to use the toilet, unable to cross the street, unable to judge danger or the temperature, unable to pick up the phone and call for help.

It’s an impassioned, heartfelt call—even a demand—for action.

An Aspie Pushes Back.

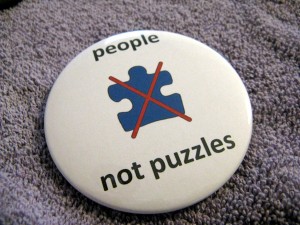

Well, many people with autism found the letter deeply offensive. They thought that it overemphasized the burden that many families face and, worse, that it dehumanized the people with autism that Autism Speaks purports to speak for. Painting an extreme picture, Wright gave the impression that all people with autism are as helpless as those with the most extreme forms of the disorder. They are all part of a “national emergency” that needs to be addressed immediately. Critics also detected a subtext implying that the goal of Autism Speaks was to rid the world of people with autism: to cure it and prevent it. And they saw in that desire a rejection of who they are.

The article was so one-sided that even a member of the organization’s science board—an fellow with Asperger syndrome named John Elder Robison—resigned his position in protest.

We do not like hearing that we are defective or diseased, he wrote. We do not like hearing that we are part of an epidemic. We are not problems for our parents or society, or genes to be eliminated. We are people.

This isn’t the first time that Autism Speaks has drawn fire like this. In 2009, the organization produced a video, I Am Autism, that also painted a bleak picture of the disorder. In it, autism itself spoke about how it is coming to take away our children, bankrupt us, and destroy our marriages. It spoke, again, as if children with autism were so defective that they were no longer “there.”

A Two-Edged Sword.

All this controversy got me thinking some more about my own experience.

On one hand, I can relate to the picture painted by Autism Speaks. I know what it’s like to be scared about my children’s future. I know what it’s like to feel worn to the bone from dealing with autism-related challenges from my kids. I know how it feels to face financial limitations or to have to explain one or another child’s unusual manner to a neighbor at the park or a stranger at the store. I know what it’s like to grieve when the news of a child’s diagnosis is delivered—I’ve done that one six times!

But that’s not the whole story. My kids aren’t problems. They aren’t the sum of their challenges. They are smart, funny, and innocent. They are perceptive, clever, and talented. The more I get to know what makes them tick, the more I am learning that autism is behind some of the things that make them so awesome.

Moving toward Acceptance.

I see how Autism Speaks’ approach can strike a chord, especially among those with young children or those struggling to embrace a recent diagnosis. In a sense, they’re saying, “Hey, we get it. It’s hard. It’s painful. It’s scary. But you’re not alone. We’re here, and we understand how tough this is.”

I don’t think, however, we’re meant to stay at this point of feeling overwhelmed, terrified, or devastated. In each autism-touched family that I know, there comes a point when everyone calms down, takes a breath, and readjusts their expectations. There comes a point when they are able to look past the label and see the beauty and goodness in their children. It’s supposed to be a natural progression, like the five stages of grief identified by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. Sooner or later, you have to get to acceptance. You can’t stay stuck in anger or depression. You have to keep moving—if only because your kids are moving, and you have to keep up with them!

By constantly banging the drum about a national epidemic, by playing the fear card over and over again, organizations like Autism Speaks inhibit people from moving to the point of accepting their children as precious gifts from God. They also are complicit in fostering a kind of victim mentality in families touched by autism. “Look at how hard our lives are. Look at how damaged our children are. Pity us! Help us!”

Who’s Talking?

In the past, I supported Autism Speaks 100 percent. I wore their lapel pin and wrist band to help raise awareness. I followed their blog. I attended seminars sponsored by them. I even raised a good amount of money for them.

But now I’m not so sure. As John Elder Robison said, I’m not sure that Autism Speaks really does speak for my kids. I don’t want my kids growing up feeling like victims. I want them to be victors. I want them to use all their gifts—even the ones that autism has given them—to show the world that people like them can make a huge difference. I want them to embrace everything about who they are, even their autism, and turn it into something that glorifies God and lifts up the people around them. And they can’t do that if they think of themselves as problems or burdens.

Autism awareness is important, but only if it leads to acceptance. Not just pity or tolerance but acceptance.