So we made it to Holy Thursday Mass yesterday again this year. It’s a pretty big deal in the Catholic Church, since it is the beginning of our Easter celebration. It’s also pretty important because on Holy Thursday we remember the Last Supper, when Jesus gave us his Body and Blood in the form of bread and wine and told us, “Do this in memory of me.”

. . . Into the Hands of Sinful Men.

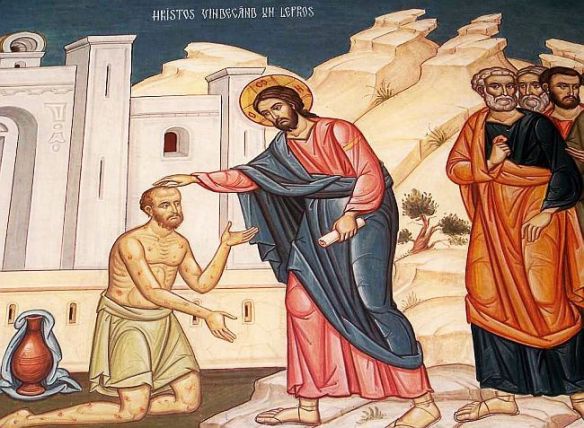

I love the idea that by saying, “This is my body . . . This is my blood,” Jesus made sure he would be present to us all the time. I’ve always loved the way that the Last Supper foreshadows the cross: in both cases, Jesus gave himself into the hands of sinful men so that he could lift them up to be with him. I find it moving that Jesus continues to give himself to us—sinners though we are—every time we come together to celebrate Mass.

Now, before we get to all the autism stuff, do me (and yourself) a favor. Let this thought sink in for a moment: Jesus continues to let sinful, conflicted, duplicitous, envious, lustful, bitter, [insert sin here] people take him into their divided hearts.

Six Sacramental Signs.

All this was in my mind on Thursday as we entered the church. I was really looking forward to a deeply meaningful, spiritual experience at the church. But alas, it was not meant to be. A couple of our kids had had a rough day at school, and they brought their agitation with them to church. One had forgotten to take her ADHD medicine, so she couldn’t stop chatting with Katie, fidgeting all over the place, and trying to engage her brothers. Another was worried about a difficult test that morning, and his anxiety worsened as the Mass went on. A third just plain didn’t want to be there, and he made sure to let everyone know it.

So there I was, trying to keep the kids from boiling over, trying not to distract the people around us, feeling more than a little uncomfortable with the way we stuck out, and feeling cheated out of my time with God.

Then it hit me.

Jesus has given these children to me. He has placed them into my hands. He knows what kind of person I am. He knows my weaknesses and my faults. He knows my selfishness and my lack of generosity. He knows my impatience and perfectionism. And still he saw fit to give me six kids with special needs. Six kids who would need extra attention. Six kids who would need a creative, flexible approach to parenting. Six kids who would need extra love to help make up for the world’s lack of understanding and acceptance.

I saw this right there in the middle of Mass. These kids are also the body of Christ. They are all signs of God’s beguiling creativity. They’re signs of his maddening ability to call forth the better part of my human nature while at the same time exposing my darker parts. They’re sacramental signs who both symbolize God’s mystery and impart his grace to everyone whose hearts are open.

In the midst of their everydayness, their struggles, and the occasional banality of their lives, there is something sacred about my kids. Like the Eucharist, their simple, unassuming appearance belies their wondrous complexity and depth. And like Jesus himself, they are a sign of contradiction, especially in the way their place on the autism spectrum evokes extreme reactions, both positive and negative. Yes, they are the body of Christ, and God has placed them into my hands. Just as Jesus is placed into my hands at every Communion line.

The Divine Risk-Taker.

I don’t know that I would take such a risk if I were God. There are a lot of men who would do a lot better at this than me. But then again, God seems to be in the risk-taking business. Again, it’s like the gift of his Body and Blood in the Eucharist. Jesus knows the risks involved in giving himself to us. He knows that not everybody will accept him with the right state of heart. He knows that nobody will ever grasp just how awesome this gift is. But none of this stops him from offering himself to us. Over and over again. In love and humility. For our sakes.

In a similar way, Jesus has seen fit to entrust these six children, these six images of himself, into my hands. He knows the risks. He knows that I won’t always be worthy of the gift. He knows that I’ll never fully understand how much he has given me. Still, he has given them to me and said, “Here, I trust you.”

At the Last Supper, Jesus told his disciples, “If I have washed your feet, you ought to wash each other’s feet.” He also told them, “Do this in memory of me.” He says the same thing to me. Every day. Through every one of my children. In every challenge and melt down and IEP meeting and therapy appointment and sensory overload.

Wash their feet.

Do it in memory of me.

And all I can do is stand in wonder that he trusts me so much.

Happy Easter, everyone.