This kind of thing happens a lot, but I don’t often share it in this forum: a passage from Scripture or an insight from prayer will speak directly to my life as an autism dad. This time, it’s an insight that came from the Scripture readings at Mass today (Sunday, February 11). So, having explained the spiritual nature of this post—at least the beginning of the post—let me move ahead.

First, the Story.

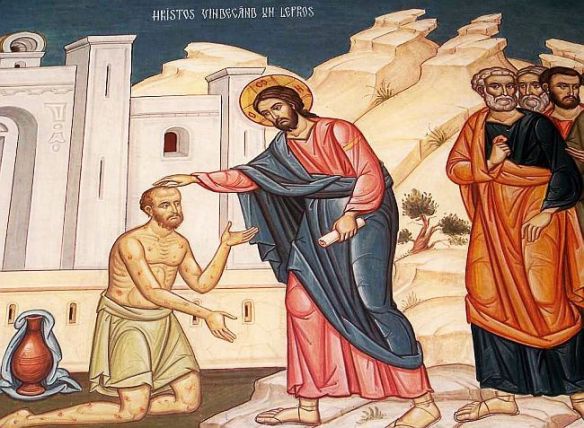

Today’s Gospel reading was the story of Jesus healing a leper. It’s in Mark 1:40-45. The man, somewhat timidly, says to Jesus, “If you will it, you can make me clean.” Jesus, in reply, touches the man and says, “I do will it; be made clean.” And the man was healed.

But then Jesus tells the man to keep this miracle quiet—only to show himself to (not necessarily tell) the priests, who had the power to release him from his exile and allow him to return to his home, his family, and the synagogue. So what does the man do? He goes around telling everyone what Jesus did.

Mark tells us that because of the man’s loose lips, “it was impossible for Jesus to enter a town openly. He remained outside in deserted places.” By touching the infected flesh of a leper, Jesus became ritually unclean, just as the leper had been. And because this fellow spread the news, everyone knew what Jesus had done. He was now barred from entering any town or village. He couldn’t even go visit his mother back in Nazareth.

A Simple Choice.

Okay, so that’s the story. Here’s what hit me: Willingly (I do will it), Jesus took upon himself the isolation that had been this unfortunate man’s lot. The ritual uncleanness had passed from the leprous man to Jesus, so Jesus could no longer be around other people any more. And without a peep, he accepted the consequences of this action. Knowingly, by his own actions, he placed himself under the judgment of the law.

What I found interesting is the simple, unassuming way that Jesus did this. There were no recriminations against the upholders of religious purity. No sense of superiority over those who enforced the law with no regard for the people they were condemning. No protest against the unfairness or extreme nature of the judgment. He quietly accepted the verdict. He willingly became an outcast so that this fellow could be reunited with his family and friends.

Outcast by Association.

There’s a parallel here for my life as an autism dad. Over the years, I have had countless meetings with teachers, administrators, school psychologists and school counselors. Along with Katie, I have pushed and pulled, schmoozed and confronted, plotted and pleaded to get my kids the help they need. I have even gotten one teacher fired and another demoted because of the way they worked (or failed to work) with my kids.

As you might expect, I have become persona non grata in a few schools. I have been identified as that dad on more than one occasion. One assistant principal became very adept at not returning my calls or e-mails. A teacher once told me, “You know, not everyone is cut out for school” as an attempt to keep me from pushing for help for my son. Another administrator grew so weary of my advocating that all sense of comity shriveled up, and every communication became unnaturally stiff and formal. It’s as if I had become an outcast myself.

I’ve done all of this so that my children could be more welcomed into the community of their classmates and into the community of learners that is their right. Of course, I’m willing to do it. I’d do anything to make sure my kids get every chance to succeed.

But before you get the idea that I’m a hero—or that I think I’m a hero—let me give some perspective.

Parting Ways with Jesus.

As I said above, Jesus became an outcast willingly. There was no bitterness in his heart against those who judged him. He felt no recrimination against the people who barred him from entering their towns. He held no judgment against his judges. There was only concern for the ones who had been excluded and demonized. He even forgave the people who crucified him.

I, on the other hand, can give in to the very same us-versus-them mentality that I have railed against when it is aimed at my children. I can issue harsh judgments about their teachers’ ignorance, blame the school administrators for their callousness, and even issue a blanket condemnation of all the neurotypicals around us—everyone, that is, except my close friends who, of course, get it.

So this is where Jesus and I part ways. Jesus feels just as badly for the people who do the judging as he does for their victims. In his eyes, everyone is a victim. They may be victims of the structures of sin in the world that convince people that they get ahead by pushing other people down. Or they may be victims of the structures of sin in their own hearts that make them demonize the “others” around them—the attitudes of rivalry and animosity that lurk inside everyone’s heart. Or, most likely, they are victims of a mixture of both.

It Starts with Me.

Of course, I will never be as pure or humble as Jesus. But that doesn’t mean I shouldn’t try. I don’t want my kids to grow up with a victim complex. I don’t want them to grow up bitter at the world. I don’t want them to develop some perverse sense of superiority to the “haters” and “judgers” out there.

It starts with me. Children learn what they live, so I need to create an environment of openness and generosity in our home. I need to model forgiveness and understanding. And because my kids can have a hard time grasping social cues and relationships, I need to be as clear and patient as possible.

This, I think, is one of the most important lessons I can instill in them. Because no matter where they go or what they do, they’ll always stand out. Maybe not all the time, and maybe not a lot, but they will. It’s inevitable; they’re too different not to. And no matter how much progress we make as a society, there will always be people who don’t understand. People who treat different people as lesser people. People who write them off. Even people who turn them into scapegoats.

If I can teach my kids to forgive and not judge, they will develop into men and women whom people will want to be around. They’ll find their communities, their homes, their tribes—places where they can thrive and make a difference.

It starts with me. But then again, it really doesn’t. It started with Jesus. He set the tone. He showed the way. And by his grace, I can too.